WASHINGTON — Project Convergence started relatively small, with limited soldier participation.

At its inception in the Arizona desert in 2020, the U.S. Army hoped to use the event to evaluate its materiel upgrades, including a potent brew of artificial intelligence, autonomy, robotics and radiating connectivity. The scale at which experimentation took place paled in comparison to the global presence the service touts.

The technology crucible, however, quickly grew.

In 2021, Project Convergence welcomed Air Force and Navy participation, highlighting the military-wide expectations of future fighting. The next year, it added international forces: Australia and the U.K. directly participated, while others, such as Canada, looked on. The endeavor, critical to shaping the Army’s future formations and employment of tech, soon became a breeding ground for Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control, or CJADC2, the Pentagon’s larger connectedness campaign.

But the blossoming left some in Army leadership with questions. Was there enough time to fully absorb the results? Was there enough time to plan successive events?

RELATED

“Digesting all of that data and analyzing what it really meant was a major undertaking,” Army Secretary Christine Wormuth told Defense News. “And frankly my concern for Army Futures Command was: ‘Are we rushing through this?’ ”

That organization helps shape Project Convergence year to year as well as bridge the so-called valley of death, the metaphorical chasm between technological development and its purchase and deployment.

The next iteration of Project Convergence — with the suffix “24″ — bucks the annual approach amid greater emphasis on smaller, cumulative demonstrations in the preceding months. When it’s showtime, the project will offer a grander setup, reflecting the Army’s transition to large-scale combat operations and potential international battlefields of the future, both service and defense industry officials told C4ISRNET and Defense News.

“It would be foolish, in my view, to spend the time and resources to do that kind of complex experimentation and not give ourselves the time to get the lessons and the insights out of it,” Wormuth said. “It’s not activity for activity’s sake.”

Californ-AI

Project Convergence 24 will be executed in two phases, from a pair of locations and with previously uninvolved partners.

The first will be at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, California, with eyes locked on the Indo-Pacific. The Biden administration considers the region critical to international stability and trade; it is home to some of the world’s largest militaries, namely China and India, as well as some of its largest ports.

Operations there will concentrate on the air, sea, space and cyberspace domains, as well as focus on interservice cooperation, offensive and defensive fires, and ensuring the right sensors deliver the right information to the right force at the right time, Lt. Gen. Ross Coffman, the deputy chief of Army Futures Command, told Defense News in an interview ahead of the Association of the U.S. Army’s annual conference.

Fort Irwin, California, will serve as the epicenter of the second phase, which will zero in on the land domain and involve foreign troops.

“This is an Army effort, and it’s going to take the entire Army, the joint force and our coalition partners to really learn the lessons that we need to so that we can transform together and win on future battlefields,” Coffman said. “The lessons we learn are applicable globally. They can be applied to Europe. They can be applied to Africa. They can be applied to the Pacific.”

The service is attempting to overhaul its far-shooting weapons, air and missile defense capabilities, aviation fleet, communications systems, and more as relationships with Russia and China ice over. The U.S. Defense Department considers the former a more immediate threat, while the latter poses longer-term hazards.

The service at the same time is trying to revamp the way it develops and procures the latest gear and machinery after a variety of its modernization efforts — the sprawling Future Combat Systems program, centered on a network that connected new vehicles, drones and other technology; the Crusader weapon system, intended to replace aging artillery; and the Comanche helicopter — all foundered.

“The Army is transforming,” Coffman said. “And as we look to the future, as we look out the windshield moving forward, we really are focused on pulling together all of the incredible work by [the office of the assistant secretary of the Army for acquisition, logistics and technology] in the modernization space, and then looking forward, taking into account what’s happening in real time in Ukraine and other places, and anticipating what will come next.”

The ties that bind

Testing in the spring will feature a buffet of the defense industry’s latest developments, including robots paired with soldiers on foot, specialty drones (dubbed launched effects) putting eyes on a target for long-range fires, and a means of managing contested logistics. It will also put the Army’s networks under serious stress.

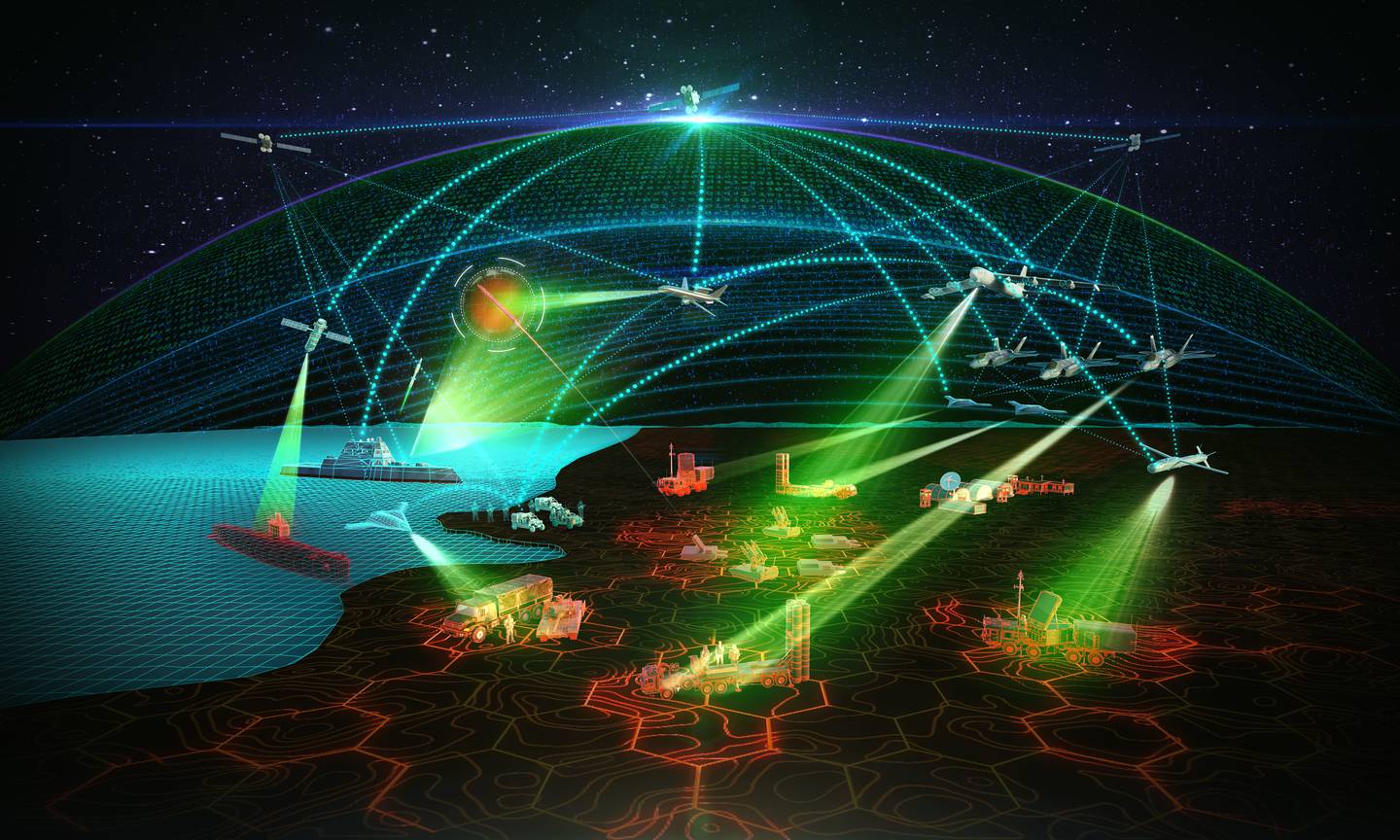

To outwit, outmaneuver and outshoot tech-savvy adversaries such as Russia and China, the Army and its sister services are betting big on CJADC2. The new era of command and control would see forces and databases across air, land, sea, space and cyberspace seamlessly interlinked, providing the best-positioned or best-equipped unit the chance to strike first and strike hard.

RELATED

“It’s an incredibly complicated task to take on, to bring all those networks together,” Bob Ashley, a retired Army lieutenant general and former director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, told C4ISRNET. “The key thing is that there’s different kinds of radios that don’t talk to other kinds of radios, and different formats of data, because we never really thought through the full interoperability for all of that stuff.”

The Defense Department requested $1.4 billion in fiscal 2024 for CJADC2. Project Convergence is often regarded as the Army’s contribution to the odyssey. The Air Force, likewise, pitches in its Advanced Battle Management System, and the Navy is workshopping Project Overmatch. Concerns about coordination have cropped up; the Air Force’s principal cyber adviser in July 2022 publicly fretted about disjointedness, and lawmakers that same year sought in annual defense legislation an audit of CJADC2 timelines and spending.

“For all these weapon systems to talk to one another, for all this data to be interoperable, that’s really what CJADC2 is about,” said Ashley, who served as a senior adviser to the Army secretary. “How do we bring all this stuff together?”

In that regard, defense companies are playing a major role. The increasingly intricate webs that need digital weaving — with data flowing from aircraft to soldier, from shore to ship, to and from command posts that quickly break down or bounce between locations — are made possible by their hardware and software.

Project Convergence 22 featured a so-called gateway where firms could test emerging kit in a relevant environment, all without breaking the bank. The initiative proved effective, according to Coffman, and will make return appearances.

“That’s the challenge we’re trying to take on. How do we go make the lightning bolts real in all these pictures that the Department of Defense likes to draw?” Adil Karim, a Northrop Grumman vice president, said in an interview with C4ISRNET. “How do we help the Army and the broader Department of Defense be more like the internet that we have in our personal life?”

Northrop Grumman is one of more than 100 companies that have participated in Project Convergence. The Virginia-based business furnished its Integrated Battle Command System, among other products.

“It’s always useful to have a real warfighter kick the tires on your capability and say, ‘Hey, could this be a circle instead of a square?’ Or, ‘Can we paint it red instead of blue?’ That kind of thing,” Karim said. “That’s always been true in exercises.”

Continued complexity

Coffman, Army Futures Command’s deputy chief, remembers when Project Convergence comprised “two enemy, two sensors, two effectors.” He was in charge of the Next Generation Combat Vehicle Cross-Functional Team. At the time, the service “wanted to prove the tech,” he said, without getting “too complex too early. So we started very small.”

That has changed.

In just three years and as many versions, Project Convergence has become a sculptor of budget blueprints, policymaking and joint force modernization. It has ushered hundreds upon hundreds of pieces of high-tech equipment into the dirt and into the hands of soldiers who may one day rely on them. It has also shed its annual rhythm — a symptom of the data avalanche produced and ultimately parsed.

“We have learned a tremendous amount. It is, I think, the biggest and most successful joint opportunity for experimentation,” Wormuth said at a September event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank.

But Project Convergence can’t just be about a splashy capstone event, the new Army chief of staff, Gen. Randy George, said during the same discussion.

RELATED

The idea is for Project Convergence to be a hotbed for capability, whether that’s a new weapon, or a novel way to tie sensors together, or how formations might fold in automaton assistance.

Much of what is demonstrated successfully there ends up growing in other exercises and activities in Europe and the Indo-Pacific, where it can then translate to real-world firepower.

The Army is “trying to look at this as continuous transformation,” George said. “What we want to do is tie all the pieces that we’re learning together and make sure we’re doing this in a continuous fashion, and kind of spinning it off.”

Colin Demarest is a reporter at C4ISRNET, where he covers military networks, cyber and IT. Colin previously covered the Department of Energy and its National Nuclear Security Administration — namely Cold War cleanup and nuclear weapons development — for a daily newspaper in South Carolina. Colin is also an award-winning photographer.

Jen Judson is an award-winning journalist covering land warfare for Defense News. She has also worked for Politico and Inside Defense. She holds a Master of Science degree in journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Kenyon College.